Archive for the ‘Normandy’ tag

Veterans Day

These week we celebrated Veterans Day in the United States to honor those who have served the country and those who are still serving. As we remember our living veterans let us not forget those who are no longer with us. As a poet once said: “All gave some, but some gave all.” You can find information about the various military cemeteries in Normandy, France by linking to them from the links provided on this site. If you link to the American Cemetery, here is some of what you will find:

The Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in France is located on the site of the temporary American St. Laurent Cemetery, established by the U.S. First Army on June 8, 1944 and the first American cemetery on European soil in World War II. The cemetery site, at the north end of its ½ mile access road, covers 172.5 acres and contains the graves of 9,387 of our military dead, most of whom lost their lives in the D-Day landings and ensuing operations. On the Walls of the Missing in a semicircular garden on the east side of the memorial are inscribed 1,557 names. Rosettes mark the names of those since recovered and identified.

The memorial consists of a semicircular colonnade with a loggia at each end containing large maps and narratives of the military operations; at the center is the bronze statue, “Spirit of American Youth.” An orientation table overlooking the beach depicts the landings in Normandy. Facing west at the memorial, one sees in the foreground the reflecting pool; beyond is the burial area with a circular chapel and, at the far end, granite statues representing the U.S. and France.

Pegasus Bridge –Part Two – Mission Success

At seven minutes after midnight on June 6th 1944, the gliders cut loose from their Halifax bomber tow-planes and began their silent descent into Normandy. The first three gliders made controlled crash landings at sixtteen minutes after midnight in the narrow strip of land between the two bridges and came to rest within meters of the bridge over the Caen Canal. They had achieved complete surprise, but with the hard landings, the occupants of the gliders were temporarily stunned. They quickly recovered, and as they had practiced on numerous occasions, they regrouped and jumped into action to overwhelm the few sentries on the bridge. Major Howard established his command post and pushed his men forward into the nearby villages of Benouville and Le Port to set up road blocks on key junctions to defend against an expected counter-attack. Within less than 20 minutes they had achieved one of their primary objectives in seizing the Canal Bridge, but at a high cost: all three platoon leaders and several of the non-commissioned officers were casualties. Now it was up to junior leaders to complete the rest of the mission – “hold until relieved.”

On the other side of the narrow strip between the canal and the Orne River, two of the gliders landed near their bridge, but the other mistakenly landed over two kilometers away. Despite the loss of one third of their strength, the remaining two platoons succeeded in seizing the river bridge. With the bridges secure, the engineers were disarming the explosives that were set by the Germans, Dr. Vaughn was setting up his aide station, an d Major Howard’s radio operator was sending the success signal: “Ham and Jam” onto higher headquarters. Then, just before 0100 hours, the paratroops of the British 6th Airborne began to drop from the sky. One of their battalions had the mission to join Major Howard’s D Company at the bridges. Like all the paratroopers that night, they were scattered and mis-dropped away from their intended drop zones. Nevertheless, the battalion commander, decided to proceed to the bridges even though he had only gathered about one third of his force. Isolated groups of paratroopers would infiltrate into the British lines throughout the night.

Meanwhile the Germans were preparing to counter-attack as they were trained to do. Their experienced commanders knew that it was best to launch an immediate attack before the British could set up a defense. One of the regimental commanders from the 21st Panzer Division, Colonel Von Luck, put his men on alert in the vicinity of Caen, but could not proceed without orders. The German high command had maintained tight control on all their armored formations and most even required approval from Hitler himself before they could be employed. Approval would be slow to come; however, small advance panzer elements were near the vicinity of the canal bridge, and they started a probing attack. Although they were not exactly sure of the situation a few tanks and infantry in self-propelled vehicles slowly clanked toward the bridges. As they proceeded, one of the British sergeants positioned himself with a PAIT gun, a crude anti-tank weapon. Sergeant Thorton courageously waited until he had a good shot and was able to knock the lead tank out of action. Fearing that the British had additional anti-tank capabilities, the Germans decided to hold off until they could get a better picture of the situation in daylight; nevertheless, they kept up infantry probes and their snipers engaged targets in and around the bridge. Realizing the importance of the bridges, the Germans mounted other attacks throughout the night including using a river gunboat and frogmen. Again using only the light weapons they had brought with them and some of the German weapons that they had captured, the British held off these advances throughout the night and into the morning.

At around 0730, the British 3rd Infantry Division accompanied by Commandos began landing on Sword Beach. As they proceed inland, they met more determined resistance at prepared strong-points. The 21st Panzer had finally been ordered into the battle and was proceeding in the direction of the beach. Further counterattacks on the bridgehead took their toll, but the glider men and the paratroops held on. Then at about 1300 hours, they heard the sound of bagpipes. It was bagpiper, Bill Millin, leading the way for Lord Lovat’s British Commandos who were bringing with them British armor and heavy weapons. With their arrival, Major Howard could now say that he had fully accomplished his mission; however the price in causalities was heavy. History now remembers this action as the Battle of Pegasus Bridge and the bridge was so named in honor of the Pegasus insignia of the British Airborne.

Here is a link to a Google map of the bridge today: Google Map Pegasus

The Normandy Campaign Draws to an End

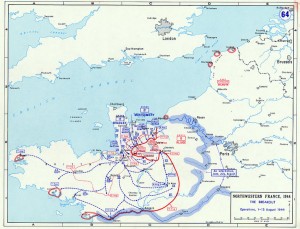

Sixty-five years ago this month, the Normandy Campaign was coming to an end after almost ninety days of brutal combat between the Allied armies and the German Wehrmacht. It began on June 6th, D-Day when British and American paratroopers jumped into the Cotiten Peninsula to secure key terrain and disrupt the Germans in advance of the assault divisions that landed on five beaches stretching for fifty miles along the coast of Northern France. Their mission was to secure a lodgement, destroy the German forces, and liberate Europe from Nazi tyranny. Although there was bitter fighting right from the start of the invasion, it only grew more intense over the next few months as they fought in the Bocage of the peninsula which was a patchwork of hedgerows. The hedgerows provided a natural defensive position from which the Germans could effectively blunt any Allied advance, and they successfully used machine guns and artillery to great advantage. Despite the Allied advantage in air power and naval gunfire , the Germans put up a stiff resistance. Their army was well trained, had combat experience, and many units, specifically the SS, were fanatical fighters who were dedicated to the Nazi regime.

Over the next few months, Allied commanders launched a series of attacks and utilized their superior air and naval forces to prepare the advance. Tragically, there were many occasions where incidents of friendly fire took place as bombs fell short of their intended targets, and Allied soldiers were killed or wounded even before the operations commenced. Yet they remained fixed on their mission, and demonstrated resilience to continue to pursue the Germans relentlessly. Resilience was crucial to the success for the Allies. It is the simple quality of an organization or individuals to overcome setbacks, and spring back so they can move ahead towards their intended objectives. Time after time, Allied soldiers and their commanders were able to overcome significant losses and rebound in spite of them.

As the weeks past, the Allies continued to bring more men and equipment into the fight while the Germans could not replace their losses. Among the German losses were some senior commanders, include Field Marshal Rommel. He was seriously injured when his staff car was attacked by an Allied fighter plane while he was traveling to visit the units at the front lines of the battle. Visiting the front at the crucial points was his custom and one of the reasons why he was one of the most effective German commanders. As the German losses mounted, their ability to counter attack was diminished. Nevertheless, Hitler demanded more aggressive action from the safety of his headquarters in East Prussia. In frustration, Hitler replaced his Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal von Rundstedt, with Field Marshall von Kluge. When he arrived in Normandy, Kluge originally thought that the biggest problem for the Germans was a lack of leadership, but as he visited the front lines, he too quickly realized that the German army simply was not able to withstand the onslaught without more replacements and support. On July 20th, an attempt was made on Hitler’s life when a bomb was set off in his bunker in East Prussia, but he sustained only minor injuries. Although his injuries were only minor, he was ruthless in pursuing the perpetrators which included a number of regular army officers. Kluge was concerned about being implicated in the plot, so when Hitler ordered a major counter attack against the Americans from the German left flank, Kluge reluctantly carried out the order even though he knew it was the wrong strategy from purely a military standpoint. This attack at Mortain only played into the Allied plan as it was held in check while the newly activated American Third Army under General Patton broke out of the hedgerow country with his armored and mechanized formations to envelop the flank of the German Army. Within a matter of days, the German attack was completely contained, and the Americans were able to advance almost unopposed into the German rear areas.

Patton drove his troops relentlessly to continue their attack so that the Germans would not have time to recover. This was exactly the right strategy. He exploited success and when necessary even by-passed pockets of resistance to keep up the momentum. By mid-August many of the German units were depleted and beginning to break down under the stress of constant combat. After encircling most of the German Army, the Americans and British attempted to complete the encirclement at Falaise. The Canadians and Poles were attacking from the north towards Falaise while Patton’s Americans and the French 2nd Armored Division were attacking north intending to meet up with them. After reaching Argentan, Patton was ordered to stop his advance to avoid a friendly fire incident with the Canadians and Poles; however, the Canadians and Poles had run into determined resistance from SS Panzer units that were trying to keep the Gap open so that others could escape east across the Seine River to fight another day. In this, they were successful for awhile, but eventually the gap was closed and the Allied air forces relentlessly attacked any Germans on the road moving east. By the end of August, the remaining Germans who were not killed inside the “Falise Pocket” surrendered to the Allies. Knowing that he would be blamed for the defeat, Kluge took his life with a cyinad pill. Meanwhile, the German commander in Paris defied Hitler’s orders to destroy the city and defend it to the last man. He declared it an “open city” and so it was fortunately spared the fate of many of the smaller villages and cites in Normandy that were ruined during the preceding weeks of brutal combat. The Free French Forces under the command of General LeClerc were given the honor to be the first Allied troops to enter Paris.

With the liberation of Paris, the Normandy campaign was officially over, but price in terms of casualties and destruction of property had been great. Not just for the armies, but also for the many French civilians who were killed, wounded, or displaced from their homes that were destroyed. Almost 20,000 were killed and many more wounded. Cities like Caen and St. Lo were reduced to a pile of rubble. Many other towns were partially runied as the Germans and the Allies traded artillery barges, or when Allied bombers dropped their payloads in advance of the attack. In the process of liberating the Continent, much of it was destroyed. It is significant the the Free French Forces joined the Allied effort with the full knowledge that their country would suffer so much in the process. Following the Normandy Campaign, there would still be months of bitter fighting all through the winter of 1944-45. The Allied Supreme Commander, General Eisenhower, would be challenged not only by the Germans, but also by the infighting among the Allied commanders. However, he successfully led the coalition to complete his mission that he started on June 6th when the Germans finally surrendered unconditionally in May 1945. So, as Prime Minister Churchill aptly stated, although Normandy was not the end, perhaps it was the beginning of the end.

Learn from History: Leadership requires a vision

Sixty-Five years ago, Allied armies under the command of General Dwight D. Eisenhower stormed the beaches at Normandy to liberate Europe and end World War II. This was and still remains one of the most complex military operations ever undertaken. It was planned and executed without the help of modern communications and computers that we now take for granted. So what can we learn from these historical events of over a half century ago that could help us today? Leadership.

The successful Allied invasion was the result of superior leadership starting with General Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander, and continued all the way down to the sergeants and junior officers that led the troops into battle. While the Germans also had some good individual leaders like Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, as a group, the did not share the same vision on how they would defend the beaches. Thus, what started as a foothold on the continent by the Allies grew into a major assault that could not be contained. The leadership provided by General Eisenhower and his subordinates became a major factor as the Allies fought together as a team. The Allies were able to eventually land enough troops and supplies while the Germans could not replace their losses. After some very difficult fighting, the American Third Army under the leadership of General Patton broke through the German lines. Once the breakout occurred the Germans were about to be surrounded. Those that could escape to fight another day retreated while the vast majority were either casualties or became prisoners of war.

The same principles of leadership used by the Allied commanders are universal leadership principles that can applied even today. Given the complex challenges facing the country, it will be excellent leadership that carries us forward to a better day, just as it did sixty-five years ago.

Today more than ever, strong leadership is required to solve the major challenges facing our country and the world. Business leaders need to provide strong leadership to their organizations in a weak economy. Others need to solve major problems on energy, health care, and global warming. Although these historic leadership lessons were forged in the heat of a desperate battle on D-Day, the common element that still remains is human nature. Leadership is the skill that gets things done, solves problems and moves us to a better day. We need effective leaders at all levels and in a cross section of business, non-profit, as well as government enterprises. Thus, the same principles that were used by Allied leaders to achieve victory then, can be used today to lead us forward.

A good example of a leadership principle in action is the concept of “vision.” General Eisenhower provided a vision of his plan for a successful invasion. The plan was known as Operation Overlord. All leaders must have a compelling vision of the future. This defines where they want to go and provides their followers an element of hope of success for the future. Although this is a simple, and perhaps obvious component of good leadership, it is easier said than done. Crafting a compelling vision requires a leader to have a deep understanding of his or her operating environment, the capabilities and limitations of their organization, and a clear understanding of their strategy for moving ahead. Good leaders involve their people to help them develop their vision. This creates organizational buy-in and builds support within the organization. Thus, vision is a fundamental component of good leadership. If you plan to be a successful leader, learn from history and make sure that you have a compelling vision to inspire your followers.

The Supreme Commander: General Dwight D. Eisehhower

Gen. Eisenhower visits 101st Airborne just before D-Day on June 5th 1944 at their airfield in England

In December 1943, President Roosevelt announced that General Dwight D. Eisenhower would be designated as the Supreme Allied Commander to lead the combined Allied forces for the invasion of Europe on D-Day, June 6th 1944. Eisenhower graduated from the US Military Academy at West Point with the Class of 1915. He began his military career in the infantry and served stateside during World War I, much to his chagrin. He later was assigned to served in the new tank corps and after the war was over, developed a close friendship with a fellow tank corps officer, George S. Patton. Like many officers in the post World War I army, his career progression stagnated; however he made some close associations with mentors like General Fox Conner and later General Douglas MacArthur whom he accompanied to the Phillipines when MacArthur retired from the US Army to train the Philippine Army. Eisenhower also distinguished himself by graduating first in his class at the army Command and General Staff College at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas.

When World War II began in Europe, Eisenhower was reassigned back to the US and after a series of assignments was brought to Washington DC to serve under the Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, as the head of the War Plans Divsion. He was quickly promoted to Brigadier General in this assignment, and although he was a relatively junior general officer, he demonstrated his ability not only for planning, but more importantly for dealing with people who had strong personalities and were often senior in rank. These were leadership qualities that were noticed by General Marshall and at his urging to President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill, General Eisenhower was selected to command the first combined British and American operation for the invasion of North Africa. As the Commander for Operation Torch and the subsequent Operation Husky to invade Sicily, Eisenhower demonstrated his remarkable skill for fostering teamwork among the Allied commanders. This skill for handling the strong personalities of the different commanders and forging them into a cohesive team was the primary factor for his selection as the Supreme Commander for the invasion of France in 1944. No other general, either American or British, with the possible exception of Marshall himself, could effectively lead the coalition. Although Eisenhower’s patience was tested on many occasions, it was his ablitly to build and maintain an effective team that was more important to his success than technical war-fighting skills. He deserves much credit for the final victory in Europe for this leadership ability to forge an effective team which is immeasurably more difficult when your command is a combined Allied force. Although other generals often were getting headlines for the exploits of their units, it was Eisenhower at the helm that made the combined Allied effort effective.

You can read more about Eisenhower’s career both during and after the war at the following link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Eisenhower